For the past week I've been struggling with the first chapter of my work-in-progress (some of you know I have two works in progress, but in this case I mean the bartender book).

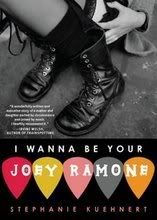

This book has had many different first chapters. To be far, I started writing it without really categorizing it (much like I did with I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone). Then I decided that I should try to write a book that was solidly YA. The partial I wrote didn't sell and I realized it's because the story was all wrong so I started it over as a book that will appeal to both adults and teens, but likely be called "women's fiction." (I really still hate labels as much as a I did as kid... so restrictive.) Anyway, the story is on the right path and I struggled so long with writing the perfect first chapter. And then I had one of those rare moments of clarity: my fighting cats jumped on my bed and I realized, Bar fight! Perfect!

Only it wasn't. My agent read it and pointed out it's flaws. I grumbled about it, pondered for a few days and realized she was right. Then I got this brilliant vision for the perfect intro that would capture the characters and the place and be chock full of imagery. I thought it would be about five pages. Right now it's a twenty-five page mess. *Sigh*

So what's a girl to do? Go back and look at drafts of old novels and reassure myself that I always suck in the beginning and things will be okay.

Well, um as it turns out the first paragraph of I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone has been virtually the same give or take a word since day one. Okay, so I knew the beginning of that book pretty well, but I struggled in other places. There was a terrible case of writer's block 2/3rds of the way through the first draft. And that book went through so many titles....

Ballads of Suburbia was a little more fun to re-examine. It only had one other title. The version of it that I wrote during my first year at Columbia College was called The Morning After, which was what I'd always wanted to name a band when I was in high school. I wrote a full draft of The Morning After and honestly, it's probably a completely different book except there is a main character named Kara with boyfriends named Adrian and Christian and she also has a more innocent fling with a guy named Liam. Her brother in that version is named Sam and I guess ultimately I decided those characters should be merged and that I liked the name Liam better. Speaking of names, Maya was Lana and Cass was Acacia (she would be Ava for most of the time I wrote Ballads actually, before one of my critique partners pointed out that I had too many names with double a's). Oh and while I use the real name of the park that the characters hang out in, Scoville Park, I give the town a fake name, Lincoln Prairie. I'm not sure what I thought I was doing there... Instead of starting the book with Kara returning to her hometown four years after a heroin overdose, I started with Kara returning to Scoville Park in the spring of her junior year after not hanging out with her friends for some time because she's been trapped in an emotionally abusive relationship with Christian. This was actually much more autobiographical than Kara's storyline in Ballads ended up being.

It starts with a very melodramatic reference to Kurt Cobain's suicide involving shotguns shoved down scratchy, song-torn throats and "exquisitely scarred poetry." *shudders* The whole thing is so overwrought and angsty, that I can't even bear to post the first paragraph, but here's a line describing the park that I still like for some reason even though it makes NO sense.

The bark of the trees smelled like ashtrays and through the sparse tufts of grass there was a muddy path that lead to where they all sat in the sun staring at a statue dedicated to soldiers who fought in long gone wars that they didn’t remember, understand what was fought for, or feel what was lost or won.

I don't why on earth I felt that tree bark could smell like ashtrays, but I still like the idea of it. Somehow it's so very Scoville Park.

Basically the first chapter of "The Morning After" is beyond cringe-inducing. I learned *a lot* from going to school for writing.... but my first drafts are still usually way off from how the book ends up.

This is the beginning of the first chapter of the first real version of Ballads, which I started writing in my last semester of grad school while my agent shopped I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone.

Now at this point I came up with the idea for starting with the epilogue and it is largely the same except for some extraneous information about Stacey and Cass (who was called Ava at the time) that I cut:

Sirens and lights welcomed me back to the suburbs of Chicago after my four-and-a-half year absence. It seemed fitting. Symbolic, considering they had also heralded my exit. And it could not have happened anywhere else: only a Berwyn cop would pull Stacey over for rolling a stop sign, cash in on her total lack of insurance, but not notice the pot smoke lingering in Stacey’s long, auburn ponytail, my cropped, black hair, and beneath both of our winter coats.

Stacey had spent two hours on the phone convincing me to come back from California for winter break that year. I planned to spend the first three nights with her, her husband, Jason, and their four year old daughter, Lina—a situation I was still having trouble grasping at twenty. My mother didn’t even know I was back yet, nor did the only other high school friend I’d kept in touch with, Ava. Stacey was the one who needed me.

Ava had turned out to be more stable than any of us, devoted to nursing school and her boyfriend of two years whom she lived with in Wicker Park (as Stacey said, “Only losers like me still live around Oak Park.”). Ava had managed to pull together a completely normal life while Stacey was a walking disaster and I vacillated in between the two of them. I had the successful-college-student, laid-back-west-coast-transplant façade, but I hadn’t stuck it out and healed like Ava. I’d run, and the reason I hadn’t risked coming home was because I feared that if I did, I’d find out that I was still the same fucked up kid I’d been at seventeen, like Stacey thought she was.

Right before we got pulled over, Stacey was saying, “God, Kara, I’m such a fuck up. The night Jason took Lina, I tried to drown myself in the bathtub.” She rolled her cerulean eyes and exhaled a dark, nicotine-tinged laugh. “Do you know how hard that is? Your body really fights to survive even when your heart is broke so bad and your mind wants to die. I laid in the tub swilling tequila for hours, till the water was ice cold, dunking my head underneath, and trying to force myself to stay down. I fell asleep in there, but I didn’t fucking die. I woke up wet and miserable and still without my kid. So I begged Jason to take me back. Told him I’d sober up, that I wouldn’t cheat again, and I’m working on it, ‘cause I need my baby with me.”

We were on East Avenue between Cermak and Roosevelt Road where there’s a stop sign, like, every block. Stacey paused at them all, tapping her brakes, then moving on. I mean, honestly, when there’s no traffic, what Chicago driver comes to a full stop? “Fucking motherfuck!” Stacey cursed. “Don’t the goddamn Berwyn cops have anything else to do? Shit!” She slapped the steering wheel hard with the heel of her hand as I turned my head to gaze at the flashing red and blue behind us.

Then there is the actual chapter one of the book (the chapter after the epilogue since my epilogue functions as a prologue...)

It’s the ballads I like best on movie soundtracks—hell, on any album. And I’m not talking about the kind of song where a diva hits her highest note while singing about love or a rock band tones it down a couple of notches for all the ladies out there (though Poison’s “Every Rose Has It’s Thorn” is a classic, by rights). I mean a true ballad, according to the dictionary definition: a song that tells a story in short stanzas and simple words, with repetition, refrain, etc. I’m talking about the punk rocker or the country crooner telling us the story of their life in three minutes, belting out that chorus a few times to remind us of the way they messed up love and success yet again. That’s the music I’ve gotta face, my own cycle of despair.

But my story is going to take a little longer than three minutes to tell even though the concept is pretty basic: the fallen girl child. Like Persephone from the book of Greek mythology I got for Christmas in second grade. Maybe I imagined myself to be Athena, but my tiny fingers traced the drawing of little Persephone, hands thrown to the air, mouth open in a scream as Hades took her away from the bright sunshine and flowery existence that she had known. Even though her mother would eventually save her, Persephone was doomed to relive her mistakes with every winter, with every chorus. And she probably never got to be the perfect, beautiful goddess she was supposed to be.

I am definitely not the girl I was supposed to be, the genius girl that my parents, teachers, and guidance counselors wanted to mold. And I don’t mean the kind of girl who works on movie soundtracks, that’s fine, I suppose. I mean, I’m a functional human being with a career path, but I’m marred. Like Persephone, I’m an ice queen on the inside instead of content like I used to be, all because I wasn’t supposed to stumble down that path, take those turns, follow those curves. And I don’t really know how it happened. It’s like one day I got out of bed and then I closed my eyes—you know, the reverse of what you are supposed to when you wake up in the morning. Starting in the spring of my sophomore year of high school, I did that every day for a little over a year.

Cue the music here. Cue Dinah Washington crooning “What a Diff’rence a Day Makes!” But that’s already been done and that’s not my ballad, mine would be something by PJ Harvey or the Screaming Trees because if Ms. Polly Jean and Mr. Mark Lanegan had a bastard child, it would be me.

I’ll begin with the setting of my movie, what you’d see as the opening credits rolled: Oak Park, Illinois. Oak Park isn’t one of those suburbs—you know, the type with no grid system, no streets or avenues, all courts and lanes that twist through subdivisions, which center on a strip mall or a manmade lake. No, it’s nothing like that. It doesn’t have what Maya’s grandmother would call “ticky-tacky box houses”—you know, where the only thing that varies from one house to the next is the paintjob. Pale blue, pale gray, and a bunch of other shades of pale that god knows how you tell apart at night, especially if you’re drunk or stoned. I’ve heard stories about kids walking into their neighbors’ houses, accidentally climbing into bed with their friend’s sister, and getting the cops called on them. But I don’t know anything about it first- or even second hand.

‘Cause I didn’t grow up in one of those suburbs with wide lawns and narrow minds. Even though Hemingway coined that phrase about Oak Park, I’ll give it more credit that that. The lawns were broad and beautiful, true, but the people kept their minds open for the most part. I just can’t say the same about their eyes—not when it came to their kids. But, you know, it was the early nineties and there was a recession and property taxes were high and the kids needed stuff—well, we needed something and we let stuff be that thing. Anyway, everybody’s parents seemed to work long hours in Chicago, that’s where their minds and eyes were most of the time.

Of course, we didn’t live in one of those suburbs with an hour commute into the city—in fact, you can just cross Austin Boulevard and there you are on the west side of Chicago. But Oak Park is definitely not the city, which made a big difference to me because I lived on the south side of Chicago in Morgan Park until the summer before second grade when my dad got promoted. My brother, Liam, was about to enter kindergarten and my parents decided he should do so in “better public schools” now that they could afford them. Even though I didn’t really remember the old neighborhood, I claimed it as my real home for years because I didn’t want to be a suburban kid. It felt like a stigma I didn’t deserve. I mean, I remember that winter when Maggie Young, the most popular girl in the class of 1990 at Washington Irving Elementary, came up to me and asked if my coat had a YKK zipper. When I checked, responded that it didn’t, and Maggie made it into another reason to shun me—we were seven, for fuck’s sake!—I knew I could never be one of those kids from the suburbs.

The final book version of the first chapter begins with:

The summer before I entered second grade and my brother Liam started kindergarten, Dad got the promotion he’d been after for two years and my parents had enough money to move us from the south side of Chicago to its suburb, Oak Park.

Then I describe Oak Park briefly and we go into a scene with Maggie Young--an actual brief scene not just Kara's narration of it.

In the original first chapter, Kara sounds a lot more like Emily from I Wanna Be Your Joey Ramone, which is fair because I'd just finished that book, so I was stuck in her voice. She also explains a lot, tells instead of shows, which is a MAJOR first draft problem for me, but I also think it's part of the process for me to get to know the characters. I needed to know that Kara was the bastard child of a PJ Harvey and a Screaming Trees song. (I actually wrote that down on a sticky note somewhere and listened to both of those artists repeatedly during revisions.) Like I wrote those few lines in the epilogue about Cass/Ava because I needed to know that she became a nurse. I needed to know that Kara wanted to be Athena but was drawn toward Persephone... though actually that was also me. The original version of Ballads had more references to Greek Mythology that I cut because I thought that was better saved for another book.

Actually, now that I've gone through this whole analysis, I'm not sure I feel better. I'm half-worried that the newest version of the first chapter of my bartender book will end up cut to pieces.... though wait, didn't I want to trim it down? Maybe this will help me. I guess I should go find out.

As for my fellow writers out there. Do you write crappy first drafts? Do you do a lot of voice-heavy telling instead of showing like I do? Or what are your early draft bad habits?